From the Archives: International House Opens

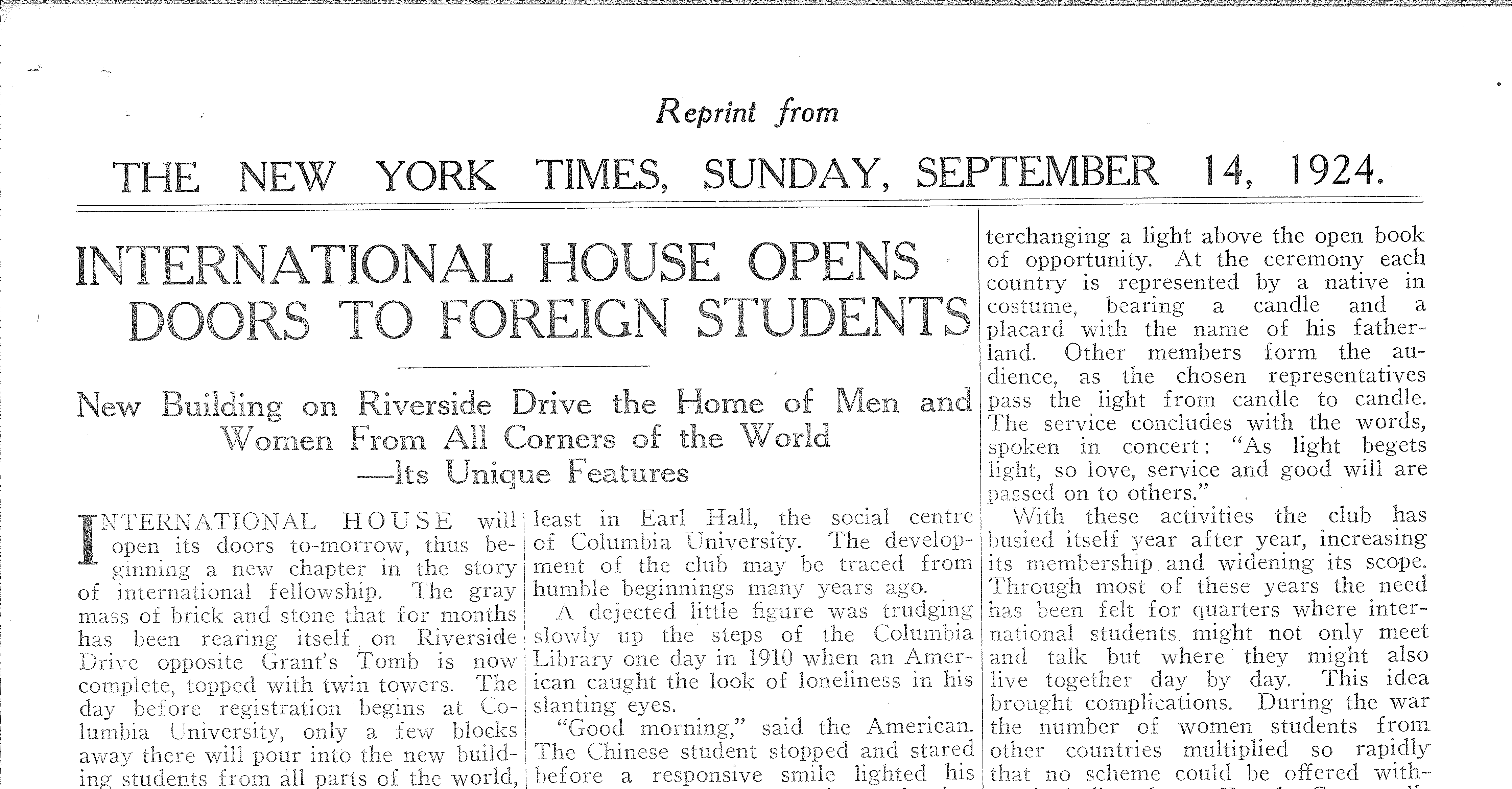

Reprint from

THE NEW YORK TIMES, SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 1924.

INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OPENS DOORS TO FOREIGN STUDENTS

New Building on Riverside Drive the Home of Men and Women From All Corners of the World — Its Unique Features

INTERNATIONAL HOUSE will open its doors tomorrow, thus beginning a new chapter in the story of international fellowship. The gray mass of brick and stone that for months has been rearing itself on Riverside Drive opposite Grant’s Tomb is now complete, topped with twin towers. The day before registration begins at Columbia University, only a few blocks away there will pour into the new building students from all parts of the world, for International House is to be a home to all of them. Already Japanese and Finns, Greeks and Hindus, Poles and Australians are hurrying around the building in anticipation.

International House is unique in its line, in the worldwide interchange of students that has gone on with increased vigor since the war, even remote colleges develop the flavor of internationalism. Wherever foreign students have penetrated, cosmopolitan clubs have usually been formed. Clubhouses have appeared with them. London may boast one of the finest, “Student Movement House,” a roomy dwelling overlooking Russell Square, offers a center for the gathering of a race. At any time of the day, an assortment of accents and skins may be found there—students in search of friends or a warm place for study. In the evening may be heard deep discussion of the affairs of nations. But Student Movement House might be tucked into a corner of International House, in which will be multiplied many times the possibilities of any existing institution for reaching the students of all lands. Besides, it will house under one roof men and women of more different countries than perhaps any other structure in the world.

Three buildings with separate walls, under one roof, constitute International House. On the river’s side is the dormitory for women, with valet service and sewing rooms, and accommodations for 125 women. The men’s dormitory, 400 rooms, faces on Claremont Avenue, with tailor shops and barbershops and a bazaar on the ground floor. Each has its reception hall and two rooms in common on each floor. In addition, there is a modern theater, an assembly hall, seating 1,000 people, for meetings, lectures, forums, theatricals, dances, and motion pictures. There are smaller rooms, too, for such purposes, and committee rooms for meetings of a national and international character.

Rooms Typically American.

The refectory offers tea-room and cafeteria service, with arrangements for large dinners and kitchenettes where student groups may prepare their own spreads. There are a gymnasium, handball courts, locker rooms, and an outdoor pool. Spacious roofs offer opportunity for exercising, rest, and play. The gymnasium manager and a health adviser have headquarters in the building. The furnishings and fittings speak of efforts have been made to depict the typically American. The assembly hall reproduces a New England meeting house; smaller public rooms have been designed according to various American periods, and the 525 bed chambers represent American standards of taste and comfort.

At the cost of two years of labor and $2,500,000, International House is completed. Into this home the Cosmopolitan Club steps from a cramped upper floor of a small Broadway building, with overflow privileges on Sunday night at least in Earl Hall, the social center of Columbia University. The development of the club may be traced from humble beginnings many years ago.

A dejected little figure was trudging slowly up the steps of the Columbia Library one day in 1910 when an American caught the look of loneliness in his slanting eyes.

“Good morning,” said the American. The Chinese student stopped and stared before a responsive smile lighted his features. Three weeks in a foreign land and his first “good morning.”

When he realized what the significant mark of attention meant to the stranger, it struck Harry E. Edmonds, then of the Young Men’s Christian Association secretary, that other foreign students might be in need of a friendly greeting. They proved it by their response to an invitation for Sunday afternoon tea. There were fewer than twenty-eight foreign men and women who gathered seven years ago, and came thom-sand of miles to school in a foreign land, but their opportunity for establishing contact with American life was this—an opportunity particularly longed for. They grasped their first chance with an eagerness almost pathetic.

Where They Come From.

A series of suppers followed the tea until an elaborate program of hospitality and service was evolved. Many Americans became interested in the work, and the international Cosmopolitan Club grew and flourished. Today it has members from all over the world. Of the students from abroad who flock into thousands to America and 1,500 more students and some women there are more than 850 members of the student assembly in its commodious new hall from twenty countries and representing fifty-two colleges and professional schools. Nearly one-half are from Europe. The continent’s share includes 280 members. There are also South America with 27, Australia with 23, Asia with 124, Islands of the Pacific 15, and Africa with 3. Canada’s group, 120 in number, comes from China, Japan’s delegation of 66 ranks second; India next with 60, and the Philippines with 43. Women constitute more than 40 per cent of the total membership. Over 300 are from the United Kingdom, Germany, France, China, Norway, Finland, and more.

With all this American representation in the Cosmopolitan Club, practically all creeds are counted—Brahminism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, Confucianism, and Zoroastrianism, to mention but a few. The Cosmopolitan Club has long since become much more than a mere social organization. It is the constant source of aid and advice necessary for students in a little-known land. It furnishes lists of approved lodgings, sets out work for those of slight means, and establishes much-desired contacts in many lands. From the corners of the earth, these young people come not only to acquire learning of the books but also to study America and Americans. The Cosmopolitan Club offers an introduction to that more difficult America of problems and ideals they present and discussed, and the voices of the American learn early that the rising generation will lead the world.

Symbolic of this relationship is the service the student clubs have themselves created at the annual commencement when hands are clasped over the club’s seal—two hands interchanging a light above the open book of opportunity. At the candle ceremony, each country is represented by a native in costume, bearing a torch and a plaque with the name of his fatherland. Other members from the audience, as the symbolic representatives, pass the light from candle to candle. The service concludes with the words, spoken in concert: “As light begets light, so love, service, and goodwill are passed on to others.”

With these activities, the club has boosted itself year after year, increasing its membership and widening its scope. Through most of these years, the need has been felt for quarters where international students might not only meet and talk but where they might also live together day by day. This idea brought complications. During the war, the number of women students from other countries multiplied so rapidly that no scheme could be offered without including them. For the Cosmopolitan Club that meant breaking away from the Young Men’s Christian Association, its foster parent, and starting forth as an independent organization, incorporated under its own charter. This was done. Still, the dormitory remained a dream because of inadequate funds.

Rockefellers Financed Building.

One Sunday evening, however, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. came to address the regular meeting of the club, and at the close of that meeting, International House was no longer merely a dream. Mr. and Mrs. Rockefeller had assumed the financial responsibility for its erection. Today their generosity and goodwill are manifested in the lofty twin towers overlooking the Hudson.

Now the possibilities of the club’s work have multiplied. Its efforts toward international understanding will in the first place reach out to many more students. On account of its previous limited quarters, the club had to restrict its numbers, excluding Americans in particular, except certain full-time students. Still, it recognized that the object sought required the hearty support of many American students and friends. Now it will have the opportunity to seek an increased American membership in its new home; in fact, the organization may gather to itself almost twice its present membership, some 1,500 men and women altogether. To one-third of these, it will be a home as well as a club, knitting them together in that fellowship attainable only under a common roof.

In this development, Mr. Edmonds sees the possibility of history repeating itself, as he calls to mind the fame of the learned Abelard, drawing to Paris students from all Europe.

“They came in such numbers,” says Mr. Edmonds, “and most of them had so little money that they were obliged to construct rude huts in the suburbs, of mud and fagots. They came out of the darkness of the Middle Ages. They listened to the lectures of the renowned monk. Then they talked things over among themselves. The knowledge they derived from one another in their rude huts became the light of a common understanding. Upon returning to their various countries they passed this light to their fellow countrymen, and soon the ignorance and prejudice of the dark ages gave way to the dawn of the age of learning. The Renaissance had come. May not something similar take place in our day from within the four walls of International House? As steel and stone are stronger than mud and fagots, so may we take courage to believe that International House may influence a world as the pupils of Abelard influenced a continent.”

Every activity of International House, both in club life and home life, is intended to open avenues for the fulfillment of the purpose carved in stone above its doorway: “That Brotherhood May Prevail.”